Go-Far 2018

Photo by: Alvin Ho

Crime rates tumble with more cameras and drones

By Sean Loo

Graphics by: Vanessa Goh

In Europe’s most wired nation, criminals have no place to hide. Estonia’s rise as a trendsetter in e-initiatives has been accompanied by a sharp fall in crime.

There were eight cases of murder and 37 cases of manslaughter in Estonia last year, as compared to 41 murder and 147 manslaughter cases in 2003, according to Statistics Estonia.

Overall, there were 6,929 offences committed last year, a sharp decrease from the 57,168 offences recorded in 2004.

The Baltic state’s Police and Border Guard believes that technology has made Estonia a safer place. In particular, the national identification (ID) card and smart ID application have played a crucial role in making it easy for citizens to authenticate themselves online, preventing identity theft.

The nature of crime has changed as a result of the digital ID system, said Mr Roger Kumm, head of Estonia’s North Prefectural Crime Prevention Branch.

“In the past, they (fraudsters) used a lot of counterfeit passports and fake ID cards to commit fraud and so on, but now it’s really hard to do so as the security level is so high,” Mr Kumm said.

According to the Statistics Estonia, there were 832 fraud reported last year, as compared to 2,285 fraud cases in 2003, one year after Estonia’s digital ID was first launched

Mr Kumm said: “With the advances made, ID cards and passports are now of very good quality. Forging this kind of good quality documents is too expensive. You won’t ever get the money back from average frauds.”

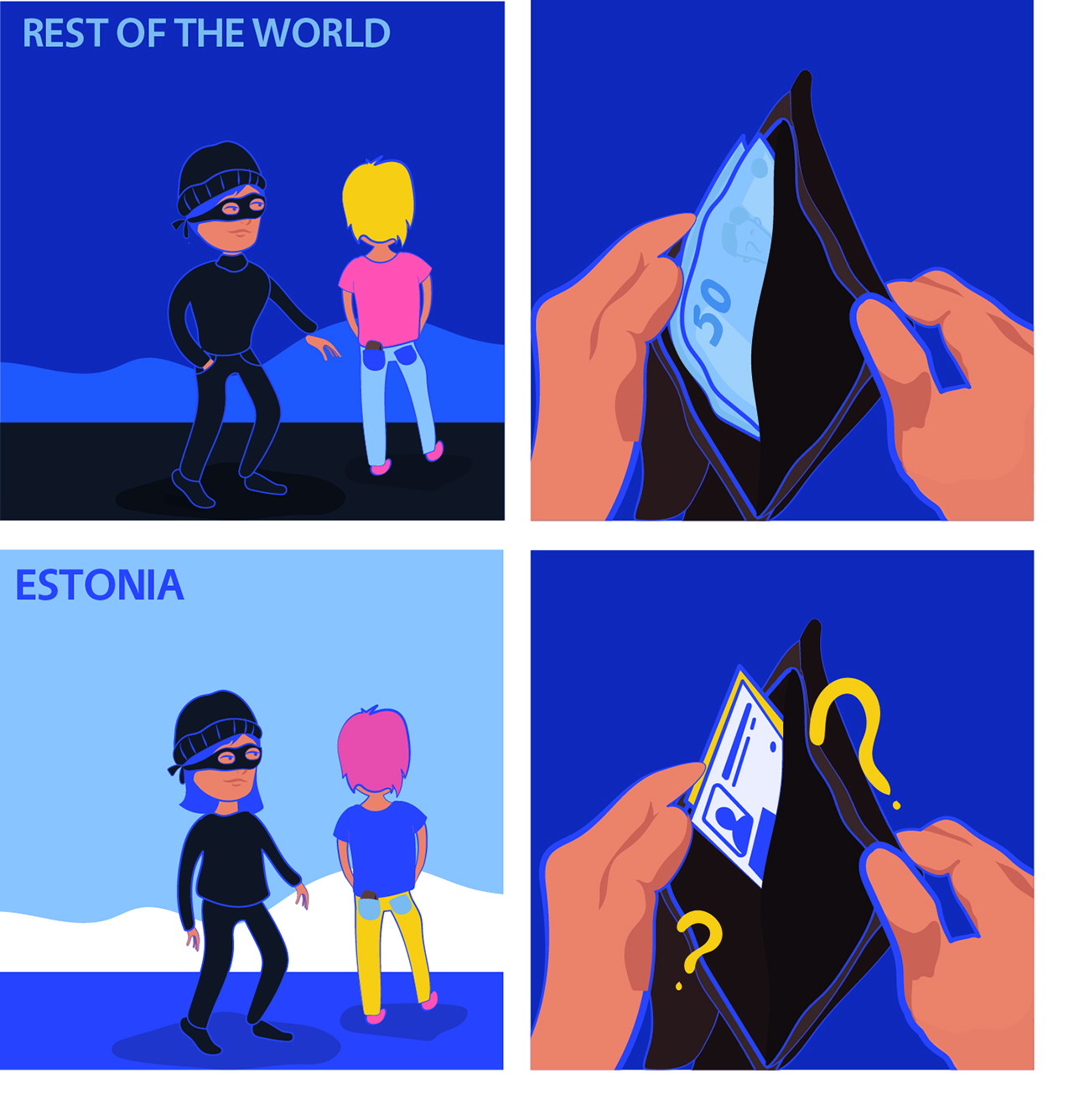

Estonia’s shift towards a digital society has also resulted in a sharp fall in larcenies, or thefts, and robberies. There were 7,834 larcenies and robberies reported in Estonia last year, an almost fivefold decrease from the 37,118 reported in 2003.

One explanation is that Estonians simply do not carry as much cash as before.

For instance, telecommunications salesman Andrian Niinemets does not carry any cash in his small, compact wallet. Mr Niinemets, who lives in Tallinn, pays with credit cards or uses online payment methods.

“I do not even remember the last time I paid for something using cash,” said the 22-year-old. “Cashless transactions are much easier and faster.”

Mr Niinemets is not alone.

A 2017 study conducted by the European Central Bank found that Estonians carry an average of 43 euros (S$70) in their wallets, which is the fourth lowest cash value among the 19 members of the Eurozone.

The study also found that 48 per cent of sales transactions in Estonia were carried out in cash, the second lowest percentage of countries in the study, behind the Netherlands at 45 per cent.

Another reason for the fall in crime rates is the sharp increase in the number of rise in security cameras on street level.

The cameras provide a high quality of video feed, enabling police to identify perpetrators quickly.

“Pickpocketing was a problem for us especially in the harbour and Old Town area,” Mr Kumm said, referring to popular tourist spots.

He added: “Now, most of our Old Town and central city is covered with either our police or private cameras (owned by shop owners). Criminals know it, and they don’t commit crime there, because they know that it will be caught on the camera.”

Law enforcement has also taken to the sky, with the Police and Border Guard utilising drones to monitor Estonia’s E eastern border with Russia.

The unit purchased nine more drones at a total cost of 500,000 euros in January to be used in enforcement activity. The drones, which are stored in backpacks, can be carried conveniently during patrols and quickly loaded onto vehicles.

Drones can prevent and respond to border incidents, and help to get an overview of hard-to-reach places, said Ms Helen Neider-Veerme, head of the Police and Border Guard’s Integrated Border Management Office.

“Whether it is an illegal border crossing, a rescue case in a water or landscape, the information collected through drones gives border guards additional opportunities to plan and conduct their activities,” Ms Neider-Veerme added.

Border guards operate ten drones at the eastern border to prevent and respond to incidents.

“Monitoring the border situation gives border guards additional opportunities to better plan and carry out their activities,” said Ms Heider-Veerme.

The police in Tallinn use drones for surveillance purposes, said Mr Kumm of of Estonia’s North Prefectural Crime Prevention Branch.

He recounted an experience where a drone aided in the arrest a group of drug dealers.

“They went to the forest to take their hidden drugs but the drone was watching their movement,” he recalled.

Estonia launched an e-Police system in March last year 2017. The system grants police officers access to information from a central database that which allows sensitive information such as a person’s criminal records to be accessed securely and efficiently.

Mr Kumm added that the system allows the Police and Border Guard to check for cross-border criminals because of the Schengen agreement.

The agreement comprises 26 European states that have officially abolished the use of passport and all other types of border controls at their mutual borders.

Despite the overall drop in crime, there has been an increase in the amount of domestic violence cases such as physical and sexual violence reported, said Mr Kumm.

However, he believes that the increase in domestic violence statistics is due to better reporting.

“Earlier, reporting domestic violence was a taboo topic. If you are telling what it’s like, you’ll be in shame for all your life,” he said.

“Now, it’s getting better and better actually. While it seems like we have a total increase in of these kinds of crimes, it was always very hushed up. But now, it’s a realistic picture.”

According to Mr Kumm, the changing attitudes are due to the introduction of full-time community police officers. Before 2014, community police officers had to juggle their community policing roles with normal police duties such as conducting patrols, but they now, they deal solely with community problems such as family disputes.

Some residents feel that the drop in crime is a result of has come about due to higher living standards.

“I feel much safer now than 15 years ago because there is less street crime,” said 43-year-old Marko Müürisepp. “There is less need for people to commit crimes.”

Ukrainian expatriate Eduard Kara, 36, describes Estonia as a country that is “safer than other European countries”.

Mr Kara, who has lived in Estonia for six years, attributes the low crime rate to the personality of Estonians.

“I feel safe in Estonia as in general, they (Estonians) are just warm and friendly people.”